We are made of the elements, and to the elements we return.

Before industrial technology, we returned our dead to the earth directly through the transformative powers of the elements. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Or fire, or water, or air, as the case may be.

Looking at the traditional body disposition practice of our ancestors offers ideas for sustainable modern choices.

Returning to the Earth

The teeming life force in fertile, microbe-rich soil is a familiar and effective way of returning the organic matter in a human body to the larger ecosystem.

Underground decomposition requires enough available land to support the deaths of the local human community. It relies on an vigorous soil culture, and green cemeteries place bodies 3-4 feet below the surface instead of the classic 6 because the aerobic bacteria are more active there. Burial is less appropriate in deserts or high altitude regions where the soil is thin.

For most people, burying an un-embalmed body in a simple, biodegradable container such as a simple wooden box or fabric shroud is the simplest, greenest approach. You may need to discuss this with your cemetery, and to learn about local laws, and the policies of public and privately owned cemeteries.

Visit the Green Burial Councils in the US or in Canada for information about green burial in your area.

Returning by Fire

The open air funeral pyres on the banks of the Ganges are an example of using fire to break down the physical bodies of our dead.

Crematoriums, the modern version of this practice, use the same principles, but burn at a much greater heat and thus combust the body more fully. The energy required to operate a crematorium is substantial, and while this is not necessarily the most ecological option, it is the most practical and desirable for many people.

Where possible, choose a crematorium that follows ecological practices to increase the energy efficiency of the furnaces and facility.

If you live near Crestone Colorado, you may be able to use the open-air funeral pyre facility built by the Crestone End of Life Project. It’s a popular choice with Buddhists and others who want a fiery send-off, with more direct participation in the cremation process.

The challenge with an open-air cremation is that incomplete combustion allows emissions such as mercury vapors from dental fillings and the residue of other non-human materials to be released into the atmosphere. The intensity of the fire of an industrial crematorium and smokestack scrubbers help limit this.

The Vikings had elaborate funeral customs, which included cremation but they didn’t do what Hollywood has since credited them with. The silver screen has given us a modernized version of their traditions, in which the body is placed in a wooden boat, set adrift, and lit on fire by a burning arrow. While it’s not historically accurate, it’s a powerful ritual action, and one that people have attempted to recreate here.

Returning to the Water

Burial at sea returns the nutrients and organic material of our bodies to the aquatic ecosystem. The water temperature determines the speed of decomposition, and it’s important to follow local regulations about getting far enough out to sea to prevent the body washing up on shore, or being caught in trawlers’ nets.

The gas released by a decomposing body can cause it to rise to the surface, so it must be properly weighed down, in either a casket or shroud specifically designed for the process.

Returning by Air

Bodies decomposing in the open air break down twice as fast as in water, and four times as fast as underground. Of course, they also nourish local animals and are returned to the food cycle that way.

In Tibet, the rocky soil is impossible to dig, there is no ocean nearby, and no trees to burn for cremation, so the bodies of the dead are given sky burials (or bya gtor, “bird-scattered”).

The family members carry the body to a special area high in the mountains called a durtro, where the body is laid out on a flat rock as an offering to the elements and the waiting vultures. In such a harsh land, all beings must work hard to sustain themselves, and the sky burial disposes of the remains in way that nourishes the birds.

New Technologies

Composting

A woodland burial plot is lovely, but what if you live in a crowded urban centre? Architect Katrina Spade of Recompose, is tackling this question with a sustainable compost renewal system for our dead.

The heart of the project is a 3-story composting tower. Bodies in simple shrouds, along with high-carbon materials like sawdust and dry leaves, are carried up the spiral ramp and placed on the top. Within a few weeks, they sink down to the bottom where a drawer allows the rich, fully decomposed compost to be removed. Loved ones are invited to take this compost and spread it in their yards and in parks to fertilize plants and trees. “In this way,” Spade says, “The dead are folded back into the fabric of the city.”

Trained Mushrooms

No matter how much organic buckwheat you eat, your body still contains the toxic residue of the modern world. Artist Jae Rhim Lee of the Infinity Mushroom Burial Project believes she may have a solution.

Lee has been feeding bits of herself –hair, nail clippings, and sloughed off skin– to a colony of edible mushrooms. She’s created a mushroom burial suit, embedded with the spores of these mushrooms, that she hopes will speed the decomposition of her body after her death.

“As the mushrooms grow, I pick the best feeders to become Infinity Mushrooms. It’s a kind of imprinting and selective breeding process for the afterlife. So when I die, the Infinity Mushrooms will recognize my body and be able to eat it,” Lee says. “As I watch the mushrooms grow and digest my body, I imagine the Infinity Mushroom as a symbol of a new way of thinking about death and the relationship between my body and the environment.”

Watch Lee’s popular TED Talk here.

Promession and Resomation

Promession and resomation are new body disposition options that may have some ecological benefits, although they still require significant energy input and and high-tech facilities. Neither are widely available.

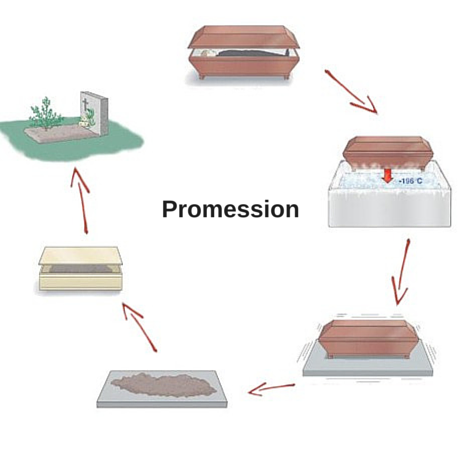

In promession, the body is flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen, vibrated it for a few minutes to disintegrate it into particles, and then freeze-dried to dehydrate it. The small amount of remaining material is organic (unlike cremated ashes) and will be metabolized by bacteria within a few months if buried in the top layers of the soil in a degradable container.

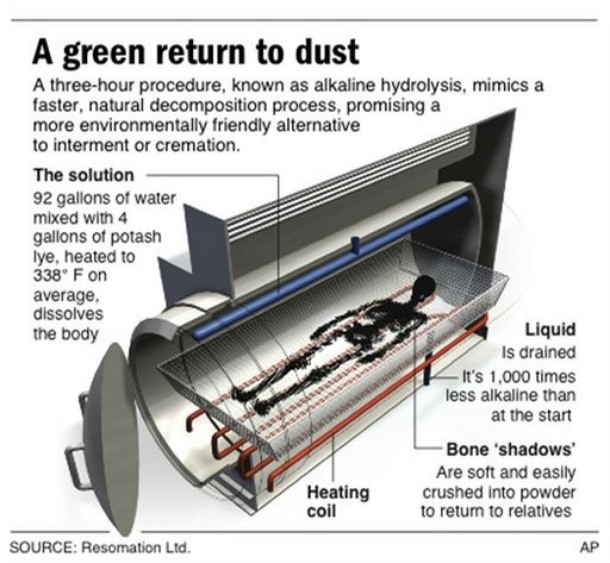

If you’ve ever had a pet cremated, it was likely done through resomation, also known as alkaline hydrolysis or aquamation. The body is wrapped in a silk shroud and placed into the resomator with water and alkali, where it is raised to a high pressure and temperature (though the temperature is 80% lower than fire cremation). In 2-3 hours, the body is reduced to an organic liquid, which can be poured on plants, and softened bones which can be crushed to resemble ashes.

Making your own decision

When considering how best dispose of your mortal remains, like most ecological decisions, there are no simple answers, It’s about finding the best option for you, today.

Let your circumstances, and personal values and priorities help you choose the disposition method most appropriate for you and your family.