_____

On August 2nd, we buried my Dad’s ashes at a tiny country graveyard in southeastern BC. It’s the final resting place of most of our relatives on my Mom’s side, with the first grave dating from the 1930’s.

We have a family dog here too, as well as a few guinea pigs. It’s a beautiful site, and one we visit often, to pay our respects and to sweep the pine needles off the graves.

One of the things I love the most about this graveyard is that we dig the holes ourselves. There’s something deeply cathartic about passing the shovel from hand to hand, carving out a spot for the one we love.

At some primal level, people know how important this task is, and the sign that we’re finished is not that the hole is big enough, but that everyone has had a turn at digging.

Children take their role in this process very seriously, and you can see them absorbing fundamental lessons about death and how to meet it.

When my niece Ella was 6, her guinea pig died. When her mom asked where she’d like to bury the body, Ella replied “At the graveyard with everyone else, of course. Because that’s where I’ll be someday. “

I like to think that this certainty about what will happen when she dies is helping Ella build a healthy relationship to death. Perhaps knowing where she’ll be, and who she’ll be with, makes the prospect of dying less daunting.

The group that gathered for the ceremony included our immediate and extended family, as well as a number of folks from another family that has also been in this area for many years. Our friendship with them began in 1912, and it’s continued for 5 generations.

I once heard an indigenous shaman use the term “ancestors of your village” to refer to the people who have known your people since long before you were born. That’s what this family is to me. In a big, busy, mobile world, I feel blessed to have people in my life with whom I can share stories that reach so far back into ancestry and place.

As we were digging, I passed around photos of our ancestors. There were lots of conversations about who looked like who, and what traits and features had been passed on from the generations before us.

Many of the people in the photos are buried in the very graves we were standing around. It was a poignant moment to associate a smiling face in an old black and white photo with the headstone at your feet.

When the hole was dug, my two young neices laid a piece of Kerr tartan in the bottom of it, invoking my Dad’s more distant ancestry, and the land where most of our ancestors originally came from.

There’s a saying that you aren’t fully an inhabitant of a place until your dead are buried in the land. As settler people, my family arrived relatively recently on this continent, and we’re only just learning how to truly be “of” this place. Having the bones of my ancestors here helps me feel that connection more deeply.

On top of the tartan, my mom poured my Dad’s ashes. We decided to forgo an urn, because my Dad was never one for frills. We thought he’d want to go right back into the ecosystem.

It’s always astounding to me how much cremated remains weigh. They’re as heavy as a stone of the same size would be. The ashes are mostly bones, and the stone-like feeling of them reminds me of our mineral nature, and how we’re literally made of the earth.

My Dad was a geologist, and when we invited people to the ceremony, we asked them each to bring a special stone. After we laid the ashes, each person came forward to place their stone on top of them, and to talk about what they loved about my Dad, and what they’d miss most about him.

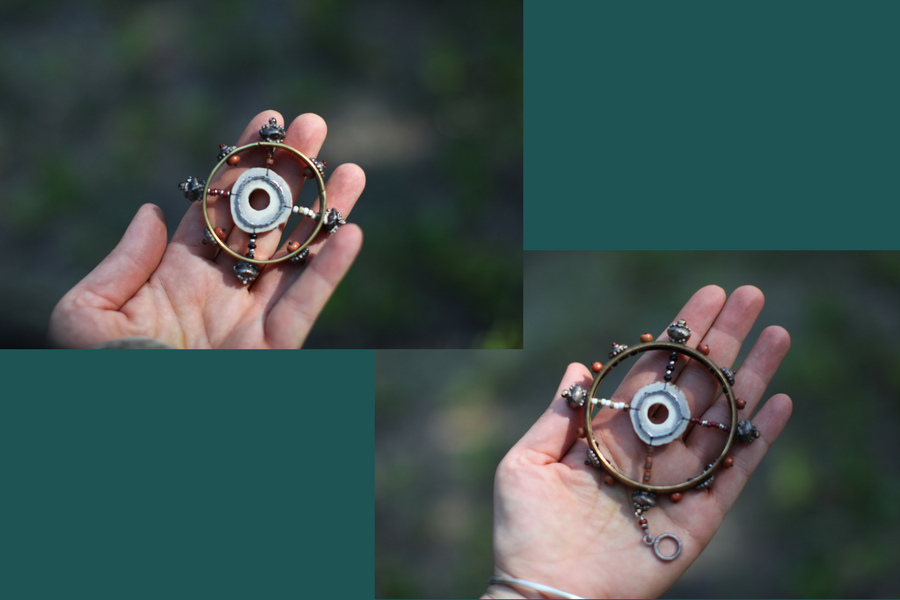

Soon after my Dad had his stroke (which was almost 7 years before his death) I had a very powerful dream. The dream told me to make two medicine wheels, as a way to stay connected to my Dad while he was ill, and then after his death.

In the dream, it was explained that these sacred objects would act like a tin-can telephone, and that I was to keep one on my altar, and the other should stay in my Dad’s room at the nursing home. I could blow prayers in mine, and they’d be delivered through his. The dream said that when my Dad died, we should bury his with him, and that it would provide a channel for him to communicate through my dreams, back to me. It was an honour to place one of them in with my Dad’s ashes.

The final addition to the hole was a bag of tiny gifts that friends and family had made for my Dad at a ceremony just after his stroke (you can read all about that ceremony here). There are literally hundreds of years of relationship and love carried in that bag, and it feels good to know that my Dad is carrying that love with him on his next journey.

There’s a saying that death should be a village-making event, and this one certainly was. My dad’s life was a gift, as was his death. I’m so grateful that we were able to give him such a beautiful send-off.

(If you haven’t read all about the ceremonies we held as, and immediately after, my Dad died, I’ve written another post about that here.)

Many thanks to my sister Julie Kerr for the photos in this post, and many of the photos on this site.

Learn more about soul-based approaches to death and loss

DOWNLOAD OUR FREE eBOOK

The Principles of Sacred Deathcare

A Guide for Soul-Based Practitioners