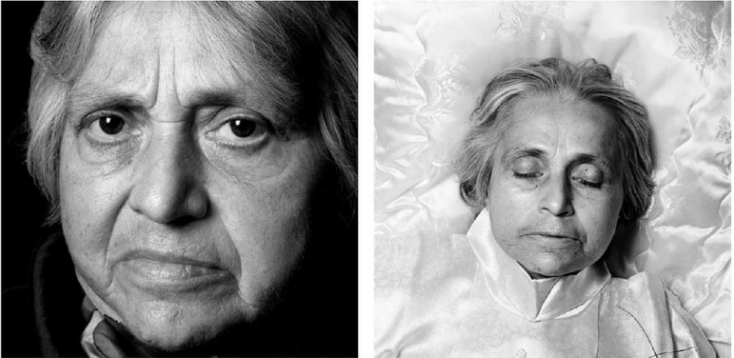

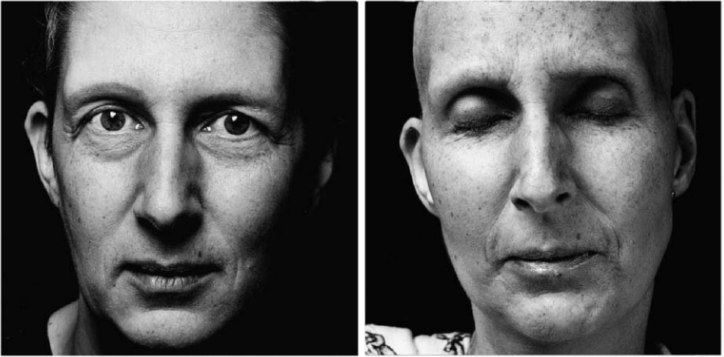

What does a dead person look like?

In 2004, German husband and wife team, photographer Walter Schels and journalist Beate Lakotta, created a documentary project called Life Before Death. Their words and photos have been seen by many, and capture the grace in dying people.

Shels and Lakotta sought permission from terminally ill patients in various hospices to accompany them during the final days and weeks of their life in order to learn something about dying. The participants consented to being photographed and portrayed just before and after their death.

In my work as a Death Doula, I often share these photos and essays with my client families, to help them prepare for an upcoming death.

Many people have never seen a dead person, and the idea of it can be frightening. These photos show that death can have a kind of beauty.

Death is hard and sad, but it doesn’t need to be scary. The more we learn about what death is, and how to meet it, the more healing and beautiful it can be.

I am grateful to Schels and Lakotta, and to all the project participants for their clarity and courage in creating the project.

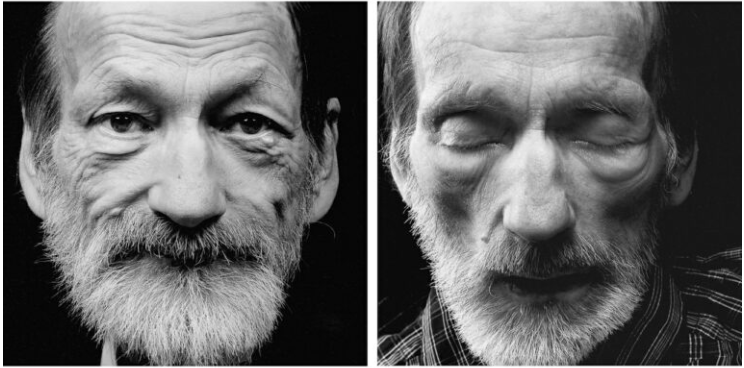

Photograph: Walter Schels/Wellcome Collection

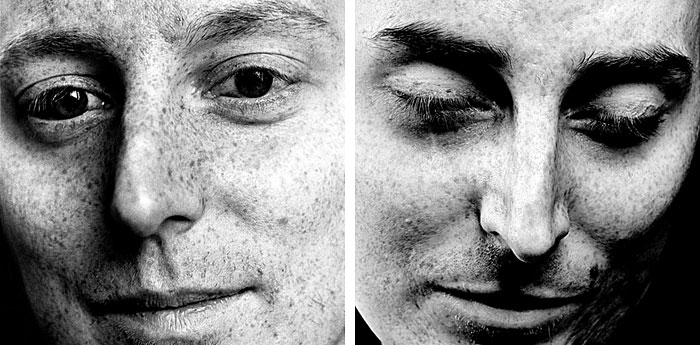

Jan Andersen, 27

Jan Andersen was 19 when he discovered that he was HIV-positive. On his 27th birthday he was told that he didn’t have much time left: cancer, a rare form, triggered by the HIV-infection. He did not complain. He put up a short, fierce fight – then he seemed to accept his destiny. His friends helped him to personalize his room in the hospice. He wanted Iris, his nurse, to tell him precisely what would happen when he died. When the woman in the room next to him died, he went to have a look at her. Seeing her allayed his fears. He said he wasn’t afraid of death.

“You’re still here?”, he said to his mother, puzzled, the night he died. “You’re not that well,” she replied. “I thought I’d better stay.”

In the final stages, the slightest physical contact had caused him pain. Now he wants her to hold him in her arms, until the very end. “I’m glad that you stayed.”

Photograph: Walter Schels/Wellcome Collection

Elmira Sang Bastian, 17 months

The tumor was probably already present when Elmira was born. Now it takes up almost the entire brain. “We cannot save your daughter”, the doctor told Elmira’s mother. Elmira has a twin sister. She is healthy. Their mother, Fatemeh Hakami, refuses to give up hope: how can God have blessed her with two children, only to take one of them away from her now? Surely God is the only one who decides whether we still breathe or not?

One sunny day, Elmira stops breathing. “At least she lived”, says her mother. She takes a small white dress from the cupboard, Elmira’s shroud. Her parents then read the Ya Sin – the 36th chapter of the Koran which describes the resurrection of the dead.

Photograph: Walter Schels/Wellcome Collection

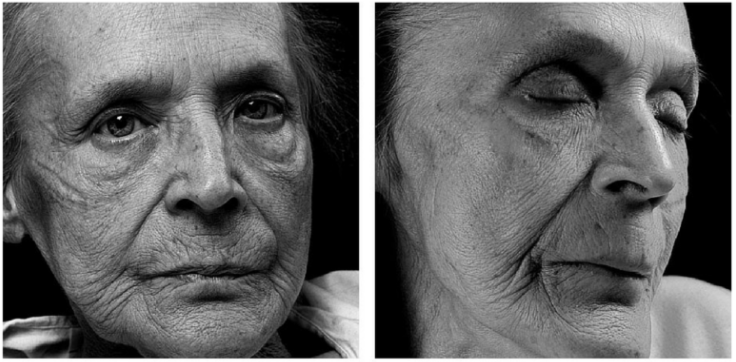

Klara Behrens, 83

Klara Behrens knows she hasn’t got much longer to live. “Sometimes, I do still hope that I’ll get better,” she says. “But then when I’m feeling really nauseous, I don’t want to carry on living. And I’d only just bought myself a new fridge-freezer! If I’d only known!”

“What I’d really like to do is to go outside, down to the River Elbe. To sit down on the stony bank and put my feet in the water. That’s what we used to do when we were children, when we went to gather wood down by the river. If I had my life over again, I’d do everything differently. I wouldn’t lug any wood around. But I wonder if it’s possible to have a second chance at life? I don’t think so. After all, you only believe what you see. And you can only see what is there. I’m not afraid of death. I’ll just be one of the million, billion grains of sand in the desert.”

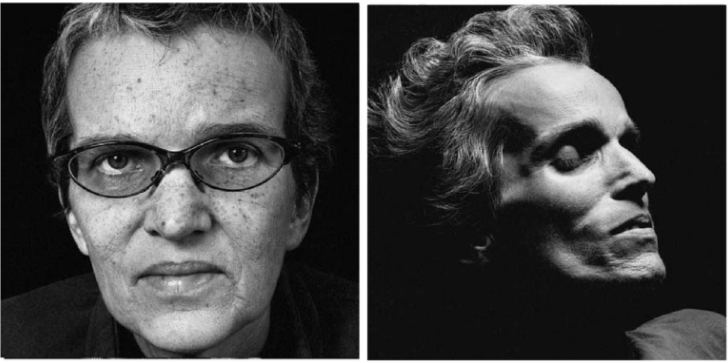

Photograph: Walter Schels/Wellcome Collection

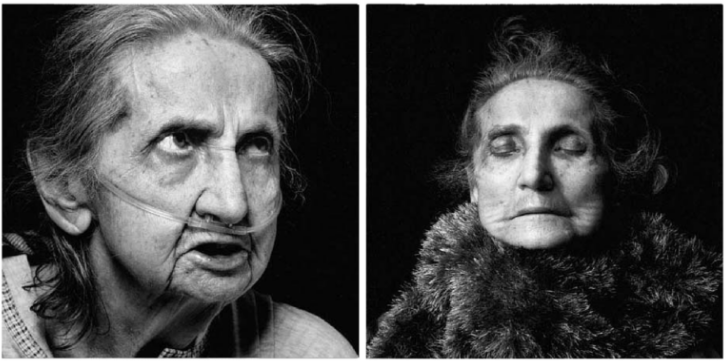

Elly Genthe, 83

Elly Genthe was a tough, resilient woman who had always managed on her own. She often said that if she couldn’t take care of herself, she’d rather be dead. When I met her for the first time, she was facing death and seemed undaunted: she was full of praise for the hospice staff and the quality of her care. But, when I visited again a few days later, she seemed to sense her strength was ebbing away.

Sometimes during those last weeks she would sleep all day: at other times, she saw little men crawling out of the flower pots who she believed had come to kill her. “Get me out of here”, she whispered as soon as anyone held her hand. “My heart will stop beating if I stay here. This is an emergency! I don’t want to die!”

Photograph: Walter Schels/Wellcome Collection

Wolfgang Kotzahn, 57

There are colorful tulips brightening up the night table. The nurse has prepared a tray with champagne glasses and a cake. It’s Wolfgang Kotzahn’s birthday today. “I’ll be 57 today. I never thought of myself growing old, but nor did I ever think I’d die when I was still so young. But death strikes at any age.”

Six months ago the reclusive accountant had been stunned by the diagnosis: bronchial carcinoma, inoperable. “It came as a real shock. I had never contemplated death at all, only life,” says Herr Kotzahn. “I’m surprised that I have come to terms with it fairly easily. Now I’m lying here waiting to die. But each day that I have I savor, experiencing life to the full. I never paid any attention to clouds before. Now I see everything from a totally different perspective: every cloud outside my window, every flower in the vase. Suddenly, everything matters.”

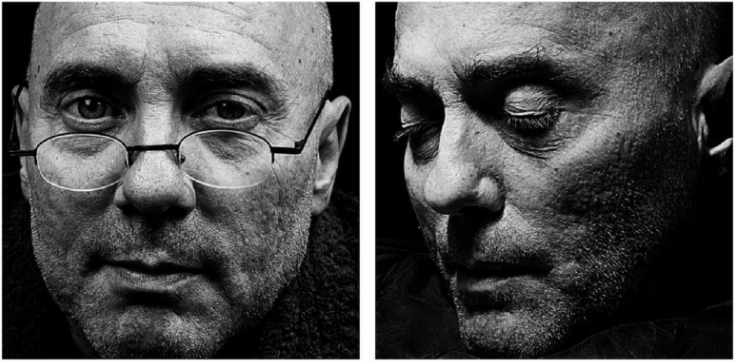

Photograph: Walter Schels/Wellcome Collection

Roswitha Pacholleck, 47

“It’s absurd really. It’s only now that I have cancer that, for the first time ever, I really want to live,” Roswitha told me on one of my visits, a few weeks after she had been admitted to the hospice. “They’re really good people here,” she said. “I enjoy every day that I’m still here. Before this my life wasn’t a happy one”

But she didn’t blame anyone. Not even herself. She had made peace with everyone, she said. She appreciated the respect and compassion she experienced in the hospice. “I know in my mind that I am going to die, but who knows? There may still be a miracle.” She vowed that if she were to survive she would work in the hospice as a volunteer.

Photograph: Walter Schels/Wellcome Collection

Heiner Schmitz, 52

Heiner was a fast talker, highly articulate, quick-witted, but not without depth. He worked in advertising. When he saw the affected area on the MRI scan of his brain he had grasped the situation very quickly: he had realised he didn’t have much time left.

Heiner’s friends clearly didn’t want him to be sad and were trying to take his mind off things. They watched football with him just like they used to do: they brought in beers, cigarettes, had a bit of a party in the room. “Some of them even say ‘get well soon’ as they’re leaving; ‘hope you’re soon back on track, mate!’” says Heiner, wryly. “But no one asks me how I feel. Don’t they get it? I’m going to die!”

Photograph: Walter Schels/Wellcome Collection

Rita Schoffler, 62

Rita and her husband had divorced 17 years before she became terminally ill with cancer. But when she was given her death sentence, she realised what she wanted to do: she wanted to speak to him again. It had been so long, and it had been such an acrimonious divorce: she had denied him access to their child, and the wounds ran deep.

When she called him and told him she was dying, he said he’d come straight over. It had been nearly 20 years since they’d exchanged a word, but he said he’d be there. “I shouldn’t have waited nearly so long to forgive and forget. I’m still fond of him despite everything.” For weeks, all she’d wanted to do was die. But, she said, “Now I’d love to be able to participate in life one last time…”

Photograph: Walter Schels/Wellcome Collection

Gerda Strech, 68

Gerda couldn’t believe that cancer was cheating her of her hard-earned retirement. “My whole life was nothing but work, work, work,” she told me. She had worked on the assembly line in a soap factory, and had brought up her children single-handedly. “Does it really have to happen now? Can’t death wait?” she sobbed

On one visit Gerda said, “It won’t be long now”, and was panic-stricken. Her daughter tried to console her, saying: “Mummy, we’ll all be together again one day.” “That’s impossible,’ Gerda replied. “Either you’re eaten by worms or burned to ashes.” “But what about your soul?” her daughter pleaded. “Oh, don’t talk to me about souls”, said her mother in an accusing tone. “Where is God now?”

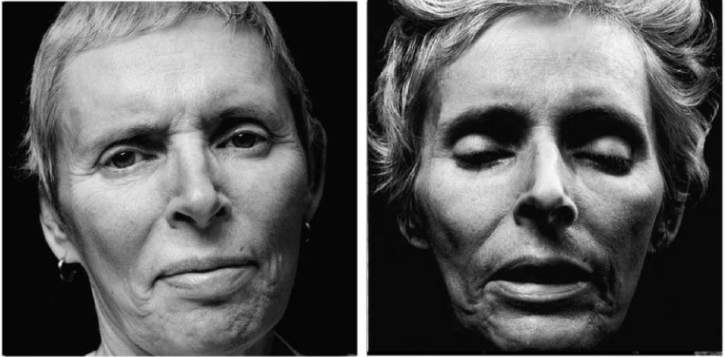

Photograph: Walter Schels/Wellcome Collection

Beate Taube, 44

Beate had been receiving treatment for breast cancer for four years, but by the time we met she had had her final course of chemotherapy, and knew she was going to die. She had even been to see the grave where she was to be buried

Beate felt that leaving her husband and children behind would be too difficult and painful if they were with her. At the moment of her death she was entirely alone — her husband was in the kitchen making a cup of coffee. He told me later that he was disappointed that he couldn’t be with her, holding her hand, but he knew this is what she had always said, that dying alone would be easier for her